Wire Gauge Sizes: What You Need To Know

Updated: May 06, 2024

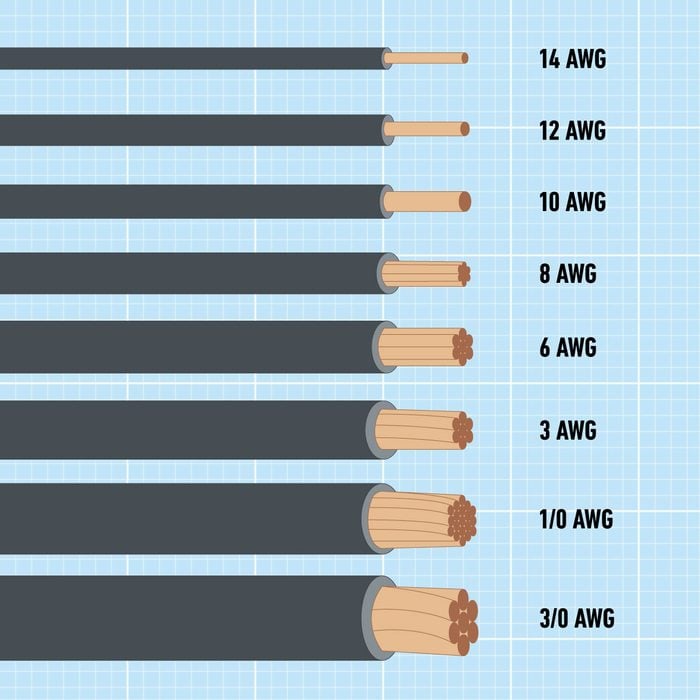

Wire gauge is a measure of wire thickness. Don't let the fact that the gauge number goes up as thickness decreases confuse you.

Pipe sizes go up with their cross-sectional diameters, and lumber sizes increase with their dimensions, so what is it with wire? Why does it get smaller as the gauge number goes up? As it turns out, it’s just a peculiarity of the manufacturing process.

Craftspeople have been making wire for centuries by drawing a metal rod through a conical opening with an exit hole slightly smaller in diameter than the rod. To make thin wire, they repeated the process with successively smaller openings until they got the desired thickness. The gauge number corresponded to the number of times they had to repeat the process. Things aren’t much different today, which is why larger gauge numbers correspond to thinner wires.

Wire gauge is an important parameter for a number of trades, including jewelry making and construction. It’s absolutely crucial when the wires carry electricity. Large-diameter (smaller-gauge) wires can conduct larger currents without overheating, but they are less flexible. Those wires are also more costly to produce, so electricians don’t want to overdo it by using thick wires when they don’t have to.

That’s why the National Electrical Code (NEC) has established current limits on commonly used wire gauges, as you can see in this checklist supplied by master electrician John Williamson, retired chief electrical inspector for the Minnesota Department of Labor and Industry.

On This Page

Types of Wire Gauge Systems

The gauge system is a way to ensure that the wire you buy in one place is identical to the wire you buy in another. That was just as important for jewelers in the Middle Ages as it is for electricians today. For centuries, manufacturers have used standardized draw plates (aka dies) with successively smaller openings to make wire.

Standards vary, however, and today commonly used systems are the British Standard Wire Gauge (SWG) system, still used in Britain and some of the British Overseas Territories; the Society of Automotive Engineers (SAE) system, which measures wire dimensions in millimeters; and the American Wire Gauge (AWG) system, which measures in Imperial units (inches). The AWG system, used throughout North America, was introduced by Joseph Brown and Lucius Sharpe in 1857, and is also known as the Brown & Sharp (or B & S) system.

How does the AWG system work?

The AWG system has 44 standard sizes, ranging from 0000 (sometimes expressed as 4/0 or “four aught”) to 40. The numbers making up the AWG system (such as 12-gauge, also called 12 AWG or #12) correspond not only to the number of dies used, but to the diameter of the wire. The diameter, as well as the wire’s cross-sectional area, must conform to specific industry standards so that it will safely carry the needed electrical load.

There’s a mathematical relationship between every gauge, based on the ratio between two defined diameters in the standard. Here’s how the sizes are related:

- Cross-sectional area: The cross-sectional area (measured in square inches) doubles for every three decreasing gauge steps. For example, 15-gauge wire has twice the cross-sectional area as 18-gauge, so two 18-gauge wires would have roughly the same current-carrying capacity as one 15-gauge wire. (You probably won’t find 15-gauge wire anywhere, though, as it’s not common in home electrical use.)

- Diameter: Doubling or halving the wire diameter (measured in inches) changes the gauge by six steps. For example, 8-gauge wire has twice the diameter of 14-gauge wire. Doubling the diameter of the wire increases the cross-sectional area by four times.

The largest AWG wire is #0000, aka 4/0, which is pronounced “four aught.” A 4/0 wire is 0.46 inches in diameter. The next smaller size is 3/0, then 2/0, then 1/0. At this point the numbers start going up (#1, #2, #3 …) even though the wires keep getting smaller. There’s theoretically no limit to the number of gauges, as long as they follow the ratio, but the standard lists gauges from 4/0 to 56 AWG.

For wires larger than 4/0, instead of being described by their gauge (diameter), they switch to units of area called “circular mils,” and cease to be referred to as AWG.

Historically, gauge numbers start at 1/0 and increase with decreasing wire size to 40, which is the thinnest wire available. Now that manufacturers can produce thicker wires than 1/0, gauge number increases with increasing size in the other direction. For example, 2/0 wire is thicker than 1/0 wire, and 4/0 wire, which is the thickest available (0.46 inches in diameter), is thicker than 3/0 wire.

Purchasing Electrical Wire

Electrical wires need to be insulated with a plastic or rubber coating, and the AWG number does not include the thickness of the insulation. You need two or more wires for most electrical applications, and you usually buy them bundled in cables. The cable jacket displays the wire gauge followed by the number of conductors (which doesn’t include the ground conductor). For example, 14/2 cable includes two 14-gauge wires and a ground wire.

Stranded wire consists of several small-gauge wires wrapped together to make a larger one, and because space between the wires is inevitable, stranded wire of a particular gauge has a larger diameter than solid wire of the same gauge. The jacket of a stranded wire displays the gauge of the wire, the number of strands and the gauge of each strand. For example, 16 AWG 26/30 wire is a 16-gauge conductor made up of 26 strands of 30-gauge wire.

Stranded wire consists of several small-gauge wires wrapped together to make a larger one, and because space between the wires is inevitable, stranded wire of a particular gauge has a larger diameter than solid wire of the same gauge. You may see stranding information listed after the AWG number when purchasing wire. For example, 16 AWG 26/30 wire is a 16-gauge conductor made up of 26 strands of 30-gauge wire.

Wire gauge in electrical work

If you do DIY electrical wiring, you may encounter situations that call for wire gauges ranging from 4 to 18, although you generally use 18-gauge wire only for low-voltage lighting and appliances. Using wire that is too thin for a particular application can cause overheating and possible fires as well as voltage drops that can cause equipment malfunctions.

Here are some common usages for the various wire gauges:

- 4-gauge: Furnaces and other 240-volt HVAC equipment that draw up to 60 amps.

- 6-gauge: 240-volt stoves, ranges and cook tops that draw from 40 to 50 amps.

- 8-gauge: 240-volt appliances that draw from 30 to 40 amps.

- 10-gauge: 240-volt clothes dryers, water heaters and air conditioners that draw up to 30 amps.

- 12-gauge: 120-volt kitchen, bathroom and outdoor receptacles, as well as 120-volt air conditioners that draw a maximum of 20 amps.

- 14-gauge: 120-volt general household lighting and receptacle light fixtures and lamp circuits that draw a maximum of 15 amps.

- 16-gauge: Light-duty 120-volt extension cords drawing a maximum of 13 amps.

- 18-gauge: Low-voltage lighting and lamp cords that draw a maximum of 10 amps.

There are some cases where you’ll use higher-gauge wire for other applications. For example, if you’re connecting a room thermostat to the low-voltage transformer on your HVAC unit, you’ll use 18- or 20-gauge wire. The same wire gauges also work for wiring most doorbells. If you do any network communications wiring in your home, you’ll use 22- or 24-gauge wire. Cat6 cable, which is the current networking standard, encloses a bundle of 23-gauge conductors.