Efficient Heating: Dual-Fuel Heat Pump

Updated: Aug. 27, 2024This double-duty unit cools and heats your home for less!

Overview

Conventional heat pumps have been heating and cooling homes for decades. In fact, about one in three homes in the United States already uses one. However, there aren’t many north of the Mason-Dixon Line because they don’t work efficiently in subfreezing temperatures. These heat pumps are great at pumping heat in or out of a house in moderate temperature swings like those found in the Sun Belt. But they’re notoriously inefficient and expensive to run in cold Northern winters.

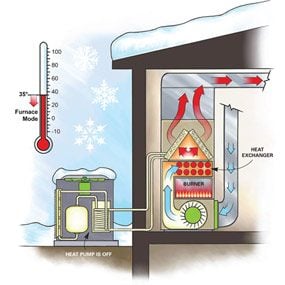

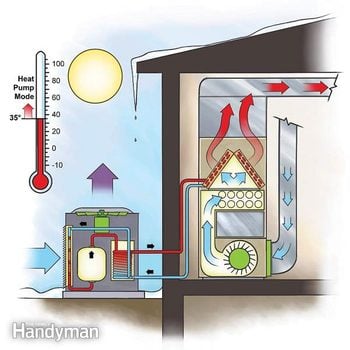

“Dual-fuel” heat pumps are different. Attached to your existing furnace, this system looks (and works, during the summer) like a high-efficiency central air conditioner. However, in those mild spring and fall months in the snowbelt, they provide cheap heat just as well as they do in the South. As the temperatures drop, the pump shuts off and tells your furnace to take over.

A dual-fuel heat pump, such as Lennox’s XP-14, will cost about 20 to 25 percent more (including installation) than an A/C. Depending on your region and fuel costs, however, it can pay for itself in five or six years.

Heating With a Dual-Fuel Heat Pump

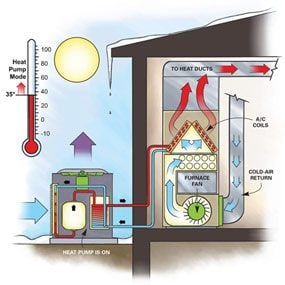

As long as the temperature is above 35 degrees F or so, a heat pump can pull heat from the outside air for less than it costs to fire up the furnace. The furnace kicks in for only the coldest months.

Heat pumps save energy because transferring heat is easier than making it. Surprisingly, even when it feels cold outside, there is still a decent amount of heat waiting to be pumped. Under ideal conditions, a heat pump can transfer 300 percent more energy than it consumes. In contrast, a high-efficiency gas furnace is about 90 percent efficient.

Check Into Tax Credits

In addition to saving money in the long run, a dual-fuel heat pump might pay you back right away. This upgrade may qualify for an energy-savings tax credit plus rebates. Ask your utility company and HVAC installer about available incentives in your area.

Pumping cheap heat out of thin air

As shown in Figure A, an air-source heat pump is basically a hybrid air conditioner. Both have a compressor (a high-pressure pump) that circulates refrigerant (a volatile gas) through indoor and outdoor coils, a network of tubes designed to facilitate the capture and release of heat. But while an air conditioner can move refrigerant in only one direction, a heat pump can force refrigerant in either direction, for heating one way and cooling the other. The pump does this by means of an extra diverting device called a switchover valve.

Run the numbers

To figure out whether a heat pump is practical for your home, you’ll need to contact a heating contractor and ask a few questions:

1. Start with a Heating and Cooling Load Analysis. Don’t trust the label on the old furnace; ask your installer to show you the math. According to some reports, there’s a good chance that your system may not have been sized correctly in the first place. Even if it was sized properly originally, subsequent home improvement projects (new insulation, new windows or an addition) can change your heating and cooling needs.

2. Check the numbers. Manufacturers use different technologies, but one number can provide an apples-to-apples comparison. For cooling efficiency, check the Seasonal Efficiency Ratio (SEER). The higher the SEER, the more efficient the unit is. Of course, units with higher ratios cost more, but every two points can reduce cooling costs by about 15 percent. (Energy Star–rated pumps are at least 8 percent more efficient than standard models.)

3. Conduct a comparative cost analysis. If you live in an area with lower-priced natural gas and sky-high electrical rates, a heat pump will not pay itself off as quickly. Your installer can factor in local energy rates (including peak and off-peak electrical rates) to calculate your potential savings and payback.

4. Ask about compatibility. Dual-fuel heat pumps are designed to work as a straightforward A/C replacement, but older furnaces probably won’t work with a new switch-hitting system. You’ll probably have to upgrade to a brand new furnace to have this system—adding a sizable chunk to the cost of the project.