How to Revive Grass: Thinning Lawn

Updated: May 23, 2019How to use an aerator and power rake to get an old lawn ready for seeding.

- Time

- Complexity

- Cost

- Multiple Days

- Beginner

- $51–100

How to Revive Grass Overview

Lawn looking thin, bare or brown? You can revitalize grass in a weekend using just one or two tools from a local rental or garden center. The power core aerator (Photos 1 and 2) loosens any compacted soil in your yard and breaks up thatch. Thatch is a cushion of old, partially decayed grass roots and stems that develop in many sodded lawns (Figure A). It separates the actively growing crown of the grass plant from the soil surface.

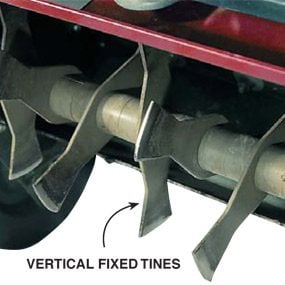

The power rake (Photo 3) is equipped with vertical fixed tines to cut the soil and prepare a thinned-out lawn for reseeding.

For you Northern homeowners whose lawns experience a hard freezing winter, the first dew in August is your signal that it’s time to aerate to ensure lush grass next spring. For homeowners in warmer or more arid states, aerate your lawn next spring to boost those warm-climate grass varieties before they go dormant in mid-summer.

How to Revive Grass: Make a Plan & Examine Your Yard

Power aerators and power rakes can usually be rented by the hour, half day or day. Because these two machines are in high demand (especially on weekends), ensure that your work plan will flow uninterrupted by reserving both machines in advance. Save some money by first renting the aerator, then picking up the power rake when you drop off the aerator. Rejuvenate your lawn using these strategies:

- Budget your time: You should be able to aerate and power rake up to 5,000 sq. ft. in three to four hours.

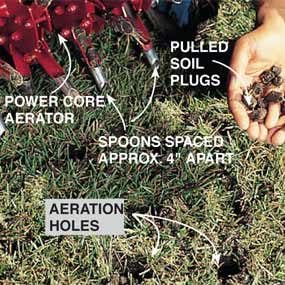

- Avoid renting aerators that are equipped with spikes and only roll over the lawn and perforate it. The core aerators that actually remove soil plugs—like the one shown—are vastly superior because they open up more soil volume.

- Recruit a buddy who has either a pickup truck or a minivan to help wrangle these heavy lawn machines home and back to the rental center. Inquire whether your rental center offers delivery and pickup (at additional cost).

- If your grass is thinned out, adopt a more aggressive plan for total lawn rejuvenation by following the steps shown in Photos 3 and 4.

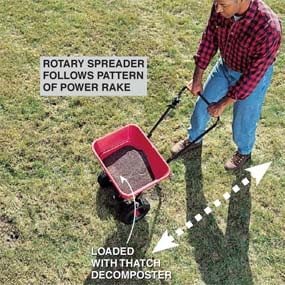

- If your lawn has excess thatch or you’ve laid new seed, use the spreader and apply decomposter mix to both accelerate the decay of thatch left in the turf and increase seed germination and rooting (Photo 5).

- Complete any plan by watering your lawn with up to 1/2 in. of water for thin lawns and 1/4 in. for bare soil. Over-watering will wash away the seed and nutrients.

If you’ve never used an aerator or a power rake, practice on an isolated section of your yard. The first time I used a power core aerator, it nearly dragged me off the lawn and into the street. My uncle still enjoys recounting that story.

How Compaction and Excess Thatch Ruin Your Lawn

The zone where grass meets soil is an amazing micro world of plant roots, bacteria, insects and complex chemical reactions. Healthy soil is soil that’s loose enough to allow air, water and nutrients to pass into it to foster plant growth. Keep these concepts in mind:

Compacted soil strangles roots

The causes are many: In existing lawns, the top 1 to 1-1/2 in. of soil becomes compacted over time from foot traffic, riding lawn mowers, high clay content and rain. New lawns often have problems—beginning with home construction or remodeling—when topsoil is bulldozed, remixed with subsoil and over-compacted. Sod lawns that are hastily laid over unevenly graded lots look good enough for the contractors to get paid, but they can manifest problems after one or two growing seasons. In both cases, the eventual outcome is choked and starved grass roots.

Too much thatch chokes the lawn

Thatch is a tightly woven layer of partially decomposed grass roots and stems that can develop over several years in the zone between the crown of the grass and the soil surface. Contrary to myth, grass clippings don’t contribute to thatch buildup, and power raking doesn’t cure it. Thatch becomes a problem when it’s thicker than 1/4 in. It’s a sign that lawns have been over-watered at night, damaged by drought, over-fertilized with high nitrogen fertilizer or that the soil is too alkaline. Thatch occurs most often in new lawns when sod is installed over dips and voids in the regraded yard or in poor or improperly prepared soil and is then incorrectly watered. Break down excess thatch by using a rotary spreader loaded with thatch decomposter mix on the lawn (Photo 5).

You can reverse the damage on a thinning lawn

Revitalize compacted soils once a year. Run a power core aerator over the lawn to pull up plugs of dirt, creating voids in the subterranean soil to provide space for and stimulate new root growth (Figure A). The slashing action of the power rake’s vertical tines slits the soil’s surface where seed, nutrients and water can combine to regenerate the lawn.

America is serious about growing grass. Since the mid-’90s, the total acreage of lawns (homes, golf courses, businesses, etc.) has exceeded the amount of land used for agriculture. Soil types and grass varieties differ by climate and region. Learn more about your soils, grass varieties and recommended lawn care practices by talking with experts at garden centers or a county extension agent. For a more complete lawn assessment, take along two 4 x 4 x 4-in. lawn samples cut from the best and worst areas of your yard. The best time to aerate and reseed cool-season grasses (varieties like Kentucky bluegrass and perennial ryegrass) is four weeks before the trees lose their leaves in your area. The best time to rejuvenate warm-season grasses (varieties like zoysia grass, bermuda grass, tall fescue and St. Augustine) is late spring. If you follow this plan, you’ll give your grass time to germinate, grow and recover from the aeration process before it goes dormant. You’ll also be able to establish a fuller, thicker lawn to help keep next season’s weed growth to a minimum.

How to Revive Grass: Aerate for compacted soils

Most lawns, whether seeded or sodded, are planted over a fairly skimpy layer of topsoil. Over time, lawn mowers, pets and pick-up football games compact the soil, making it difficult for air, water and vital nutrients to penetrate to the grass roots. Your challenge: to restore healthy soil conditions that nurture your lawn. To loosen and aerate the soil, rent a power core aerator (Photo 1). They’re available at rental centers, plus some hardware stores and garden centers.

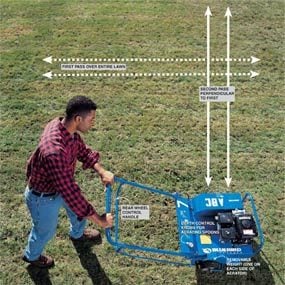

In our area, an aerator rents for about $20 per hour. This self-propelled lawn machine employs a row of evenly spaced, hollow, 3/4-in.-dia. spoons that penetrate the soil up to 3 in. deep. They pull out soil plugs, leaving a pattern of holes in the lawn that will readily absorb water, air and nutrients (Photo 1). Our rental power core aerator may differ from what you’ll rent, but they all work basically the same. Ask your rental center to demonstrate the machine’s controls and the procedures for turning and reversing, then follow these general guidelines:

-

- To avoid damaging the aerator’s spoons and scarring your sidewalks, driveways or steppingstones, run the machine across them with the rotating spoons in the raised position.

- Flag and avoid lawn sprinkler heads or you’ll risk busting them and springing a leak.

- Don’t use aerators on hillsides with a slope exceeding 35 degrees. For the safest hillside operation, go up and down hills rather than across them.

- Maximize the perforation spacing in the lawn by following the aeration pattern shown in Photo 1.

How to Revive Grass: Prepare for seeding

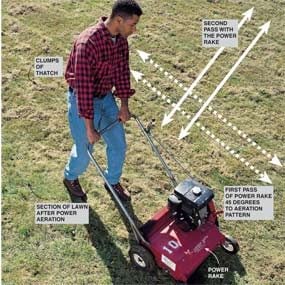

Often, older lawns that haven’t been aerated and maintained have turf that’s scraggly and thin. After power aerating the lawn, your first step to correct this problem is to rent a power rake—a gas-powered lawn machine that’s roughly the size of a lawn mower but 1-1/2 times heavier (Photo 3). They’re available at rental centers for about $15 an hour. The power rake is much less complex than a core aerator and easier to operate. Ours wasn’t self-propelled; we pushed it around the yard. It should be operated at full throttle to maximize the power of the continuously spinning, solid, vertical tines (see Photo 3, inset) that pull dead grass and lawn debris up to the lawn surface, and leave a pattern of 1/4-in. deep slits in the soil surface. Used after the aerator, the power rake will prepare the soil to receive seed and/or fertilizer. Follow these tips for using a power rake:

-

-

- Some power rakes (like ours) have fixed vertical tines for slitting the soil. These are better for penetrating any thatch and getting to the soil surface than loose, “flail-type” tines. Rent a power rake with depth controls that can be set the tines to cut 1/4 in. deep into the soil for seeding.

- For lawns with smaller areas of bare spots or thinned areas around the perimeter that you can’t efficiently power-rake, prepare the soil for seeding by using a flat-nosed shovel to chop slits in the soil 1/4 in. deep. After seeding, use the knuckles on the back of a fan-type rake to “scuff” the seed into the soil.

- Power rakes work best on lawns with even terrain. On bumpy lawns, a power rake will scalp the high spots and ride over dips in the lawn without cutting the soil.

-

Required Tools for this how to revive dead grass project

Have the necessary tools for this DIY project lined up before you start—you’ll save time and frustration.

- Hearing protection

- Safety glasses