How to Prevent Circuit Overloads

Updated: Jan. 24, 2024

Circuit breakers, overloads and your electrical system.

It happens all the time. You’re in the basement with a space heater running, and all of the sudden the lights go out and the heater stops just because someone in the bathroom turned on the hairdryer.

The problem? An overloaded circuit.

On This Page

What Is a Circuit Overload?

The power needed by the hairdryer added to the load from the space heater, the and any other devices connected to the same circuit, and all of them running at once exceeded the capacity of the electrical wiring. Here are some effective ways to charge your phone without electricity in case of a power cut or to simply lower the load!

An electrical circuit with too many electrical devices turned on can exceed the circuit limit. Circuit breakers or fuses will automatically shut off the circuit at the main panel. In most cases, the device will be a circuit breaker that trips open. In older systems a fuse will blow.

In this article we’ll tell you how to sort out the circuits in your electrical system and avoid overloads. You’ll not only avoid occasional blackouts but also avoid chronic overloading when you expand your system to include additional outlets, light fixtures or holiday lights.

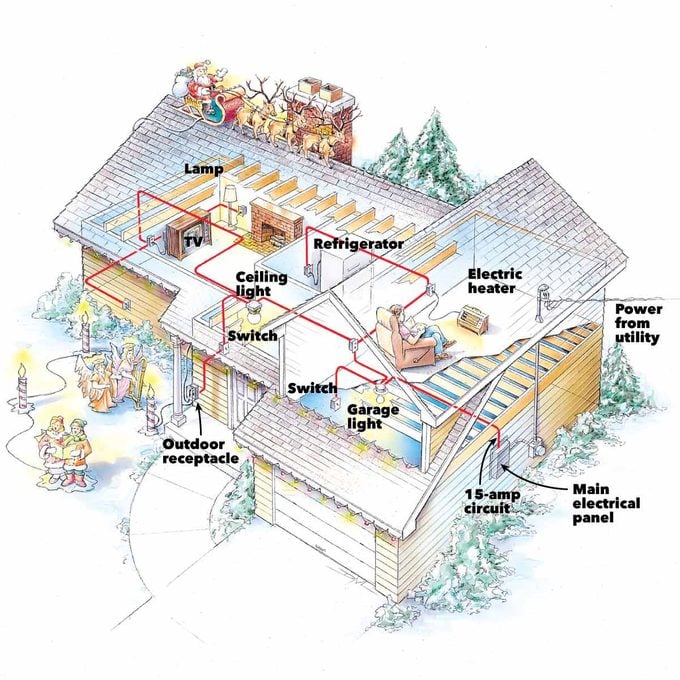

How Circuits Work in Your Home

The nerve center of your electrical system is the main panel, usually a gray metal box about the size of a cookie sheet, that typically sits in some obscure spot in a utility room, the garage or the basement. Three large wires from the utility company feed the main panel. Although you might spot the wires outside if they’re overhead, they’ll be encased in conduit inside for safety.

Circuit breakers (or fuses) in your main panel limit the power to a level that your wiring system can safely handle and funnel that power through branch circuits, the wires that run to various parts of your house. If you turn on too much stuff and the power demand on any one circuit exceeds the limits of the circuit breaker (or fuse), the breaker snaps open and shuts down the entire circuit, serving you notice that you have an overload or some other problem.

At first glance, the spider web of cables that spreads out from your main panel might look impossibly complex. Fortunately, the National Electrical Code (NEC) imposes a kind of circuit logic that simplifies the system. The circuits in the main panel are roughly divided into two types—dedicated and general purpose.

Dedicated circuits include those serving a single large-draw appliance like the furnace, range, built-in microwave, etc. (see chart).

Other dedicated circuits are for special uses like small kitchen appliances, laundry equipment and the bathroom. Because of the potentially large electrical power draw on these circuits, the NEC restricts the use of them.

Most of these should be labeled at the main panel, although they often aren’t. And don’t be surprised if you find other outlets on these circuits in older and remodeled homes. Over the years the NEC has gradually increased the number of dedicated circuits, as electrical appliance use has grown.

General-purpose circuits, on the other hand, serve multiple outlets such as lighting and most of the rest of the receptacles in your home. Normally, you can tap into one of these circuits when you need extra power or want to add another outlet. But not always. If you’re adding a receptacle for a high-power use device such as an air conditioner or electric heater, you might have to run an entirely new circuit.

Power Required for Household Appliances and Applications

(measured watts unless otherwise noted)

- Electric Range 5,000 (240 volts)

- Electric Dryer 6,000 (240 volts)

- Space Heater 1,000 and up

- Clothes Washer 1,150

- Furnace (blower) 800

- Microwave 700–1,400

- Refrigerator (not required) 700

- Freezer (not required) 700

- Dishwasher 1,400

- Central Vacuum 800

- Whirlpool/Jacuzzi 1,000 and up

- Garbage Disposer 600–1,200

- Kitchen Countertop (two circuits): Toaster 900

- Coffee maker 800

- Toaster oven 1,400

- Bathroom: Blow dryer 300–1,200

Solutions to Overloaded Circuits

The immediate solution to an overload is simple: Shift some plug-in devices from the overloaded circuit to another general-purpose circuit. Then, flip the circuit breaker back on or replace the fuse and turn stuff back on.

In practice, however, it isn’t so easy to know that you’ve found a good, long-term solution. First you have to locate outlets on another general-purpose circuit. Then you have to find a convenient way to reach it. Resist the temptation to solve the problem with an extension cord. Extension cords are for short-term use. They’re not to be used as permanent wiring or fastened into place.

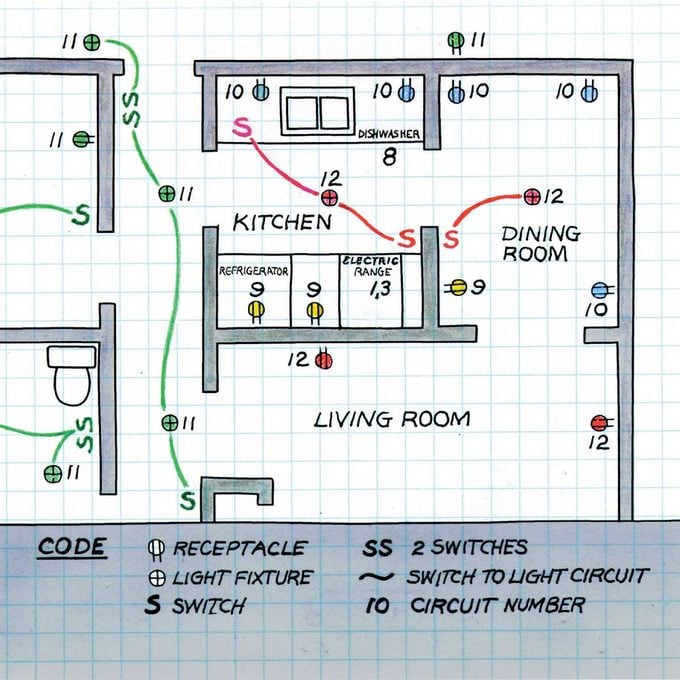

To trace your general-purpose circuits, begin with the labels on the main panel. They’re supposed to give you some idea where the circuits run. They’re usually accurate for dedicated circuits, but they’re often too vague to help you pinpoint general-purpose outlets. Chances are, you’ll have to map out these circuits yourself.

To trace a circuit, turn off its breaker at the main panel (or unscrew the fuse), then go through your home testing outlets—flipping on light switches and plugged-in devices and plugging in a test light into open receptacles.

Test both the upper and lower receptacle of standard duplex receptacles, because they’re sometimes wired to different circuits. And make sure switched receptacles are “on” before testing them. Check outdoor lights and receptacles too. Outlets that don’t work are connected to the circuit that’s off. Write your results down, or put them on a simple floor-plan diagram so you won’t forget or skip locations.

Repeat for other circuits until you know what’s what. Don’t be surprised if you find general-purpose outlets on dedicated circuits. It’s not unusual to find the family room on the same circuit as the refrigerator. (And remember to reset the clocks when you’re done!)

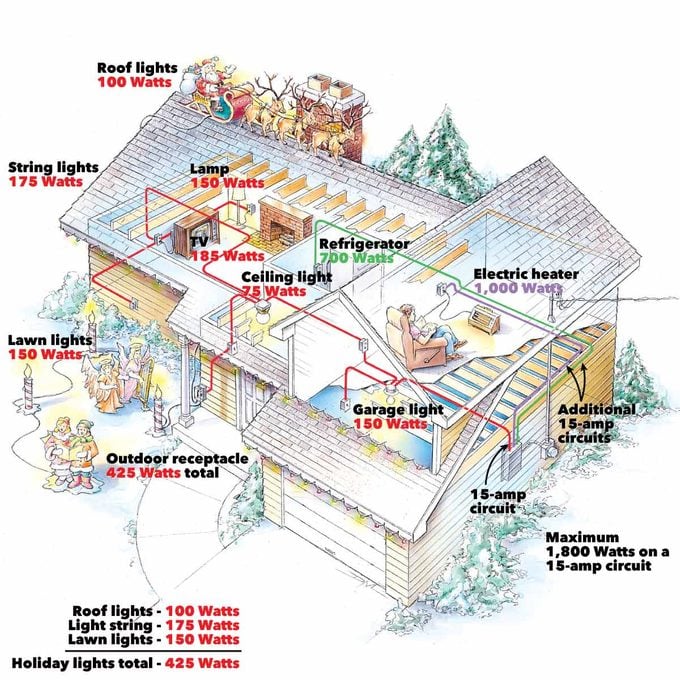

Once you’ve mapped out the general-purpose circuits (even better—all your circuits), sharpen your pencil and add up the existing electrical loads on them. The image below shows the loads of the various lights and devices that were originally connected to one of the circuits found in the image above. Learn how to calculate the electrical load.

Light bulbs usually have their wattage stamped on them. Motors are often rated in amperes or “amps” (amps x 120 volts = watts), a figure you’ll find on a plate on the motor or elsewhere on the device. TVs and other electronics usually have a watt rating on a backside label. Then figure the additional load you want to add, in this case the holiday lights.

Devices temporarily plugged in, such as a vacuum cleaner or temporarily used portable electric heater, don’t count. Devices (for example, holiday lights or an often used electric heater) with long-term uses do count.

A circuit is overloaded if: A. The total load exceeds 1,800 watts for a 15-amp circuit. (120 volts x 15 amps = 1,800 watts.) Look for the amp rating of the circuit in tiny numbers on the circuit breaker switch or fuse to determine how many outlets you can have on a 15-amp circuit. For a 20-amp circuit, the load limit is 2,400 watts. B. On a multiple-outlet circuit, you find any appliance or equipment rated at more than half the circuit rating, 900 watts for a 15-amp circuit. (These large-draw appliances should have dedicated circuits.)

Upon checking, we found that the example circuit in the first illustration here exceeded both the 1,800-watt limit for a 15-amp circuit and the 900-watt limit for any one device. The best solution to solve this overload situation is to run a dedicated circuit to the biggest load. In practice, to avoid high installation costs, professional electricians run new circuits to the appliances they can reach most easily.

In our case, a professional electrician would run two new circuits, one to the refrigerator (700 watts) and another to the outlet handling the heater (1,000-plus watts).

Practical advice: Don’t load your circuits to the maximum (figure about 80 percent). Otherwise, you’re more likely to have hassles with overloads when you temporarily plug in high-draw devices such as a vacuum cleaner (800 to 1,100 watts).

Map Your Circuits

Sketch your floor plan and draw in your electrical outlets, labeling them according to their circuit number from the main panel. Circuits 11 and 12 are general-purpose circuits.

Adding a New Outlet

After calculating the loads on your general-purpose circuits, you can redistribute the loads (plug-in devices) so no single circuit has more than 1,800 watts. This isn’t always convenient, however. You’ll often have to add a new circuit, as we did in our example, or install a new outlet to get the power where you want it.

To add a new outlet, find a circuit with sufficient capacity (following rules A and B above) that has a convenient junction box to tap into. You can sometimes find easy access to lights or switch boxes in an unfinished basement. Otherwise, look to the attic. The junction boxes in most attics (assuming your attic is accessible) are usually buried under insulation, so you’ll probably have to rake the insulation aside. (Wear a dust mask, goggles and long sleeves if you do this!) Look for junction boxes near the access hole first, or over ceiling light fixtures in rooms below. (Remember: The power must come directly to the light box, not from a switch.)

CAUTION: Electrical boxes might contain wires from several circuits. Test the wires with a voltage tester before touching them to make sure the power is off.

Practical advice: If the wiring in a box looks complicated, find a different box or call in an electrician to make the connections.

Make sure the existing box is large enough to accommodate the additional new cable. Wires packed into too small a box can overheat.

Practical advice: It’s often easier and faster to run an entirely new circuit from the main panel, rather than find and tap into an existing circuit. If you install the new outlet yourself and run the new cable back to the main panel, an electrician will make the hook-up inside the panel.

CAUTION: Working inside the main panel is dangerous. Let a pro do it.

Safe Electrical Practices Pay Off

Always apply for an electrical permit from your local building inspections department when you undertake an electrical project. The permit not only ensures that your work will be inspected for proper technique and safety but also that you’ve properly analyzed your home’s circuitry and are following a sound plan. Here’s what you need to know about overcurrent protection.